IN THE HORNED MAJESTY OF MY ANCIENT ANTLERED ANCESTRY - An Alternative Inauguration: Invoking Personal Power Rather Than Political Power Through Celebrating The Primal Shamanic Roots of Poetry

Using the act of writing itself as a practice to enter ‘Access Concentration’ & remaining undistractedly in ‘The Natural State’ while at the same time experiencing an 'altered state' of consciousness

CLICK ON THE BUTTON ABOVE TOWARDS THE RIGHT OF THE PAGE to hear a recording of John Shane reading his poem ‘In The Horned Majesty Of My Ancient Antlered Ancestry (Stark Trees Frost Fingers All)’.

We live in times in which the all-pervading nature of the mass media bombards us with more news than ever before and so much of what we read and see and hear in the news can leave us feeling dispirited and disempowered.

In the face of this onslaught of soul-crushing negativity, tuning in to our inherent creativity through creative strategies such as The Way of the Poet can help us reclaim our personal power and renew our sense of our spiritual agency in a world in which it can seem that we have no value except in so far as can be measured in material terms.

As we witness events such as the inauguration of the President of the United States, it may seem that those who have the most in material terms are examples of ‘successful’ human beings because they have found a way to dominate and control everyone else, but such people are like hungry ghosts, never satisfied no matter how much wealth and power they have acquired.

To counteract our sense that we have no value in the material world and to overcome in ourselves that same hollowness and lack of satisfaction, we need to turn inwards to discover and recover a sense of the innate wholeness of our essential being, in which nothing is lacking.

But then, from that sense of our inherent wholeness, of our inherent completeness, we need to act in the world, bringing the insight we have gained from looking within into every aspect of our lives and our environment.

Among the most ancient role models for this kind of activity of reclaiming our power, we find everywhere on the Earth, dating back to the beginnings of time, the omnipresent, shapeshifting figure of the Shaman, the archaic forerunner of the poet in the visionary use of the primordial powers of language and archetypal imagery, master or mistress of the arts of the drum & the chant, primordial maker of rituals to mark the seasons of the soul & the stages of life…

In these days, as we see photos of the inauguration of a President of the United States surrounded by billionaire oligarchs and other corporate donors, as an example of an alternative inauguration in terms of personal rather than political power, I am publishing here, for the first time, a poem I wrote many years ago in the midst of a heavy snowstorm deep in the countryside of rural England in which I lay claim to the ancient roots of my art, an art that predates the arrival of writing and has existed from the time of the very origins of the gift of language.

The poem was written when I returned home after meeting my teacher the Dzogchen Master Chogyal Namkhai Norbu for the first time at two retreats in 1978, one in London and one in Paris.

(Below the text of the poem itself you will find some notes on where and how the poem was written that provide context and commentary on the poem, and the last part of this post clarifies that what is called ‘The Natural State’ in teachings such as Dzogchen, is not an ‘altered state’ like a psychedelic experience or a Shamanic trance in which the third part of this poem was written.)

THE SHAMAN OF TROIS FRERES:

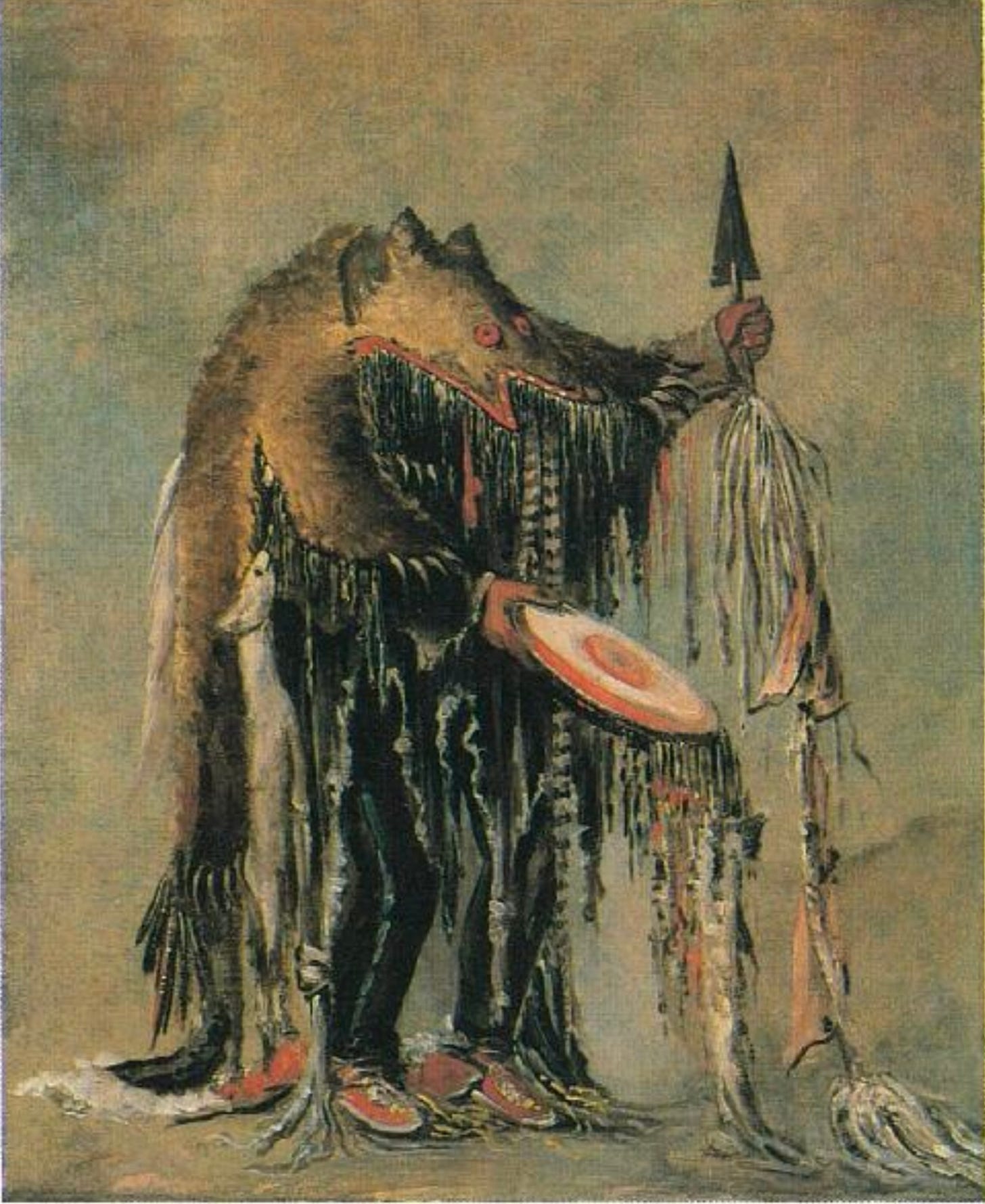

Among the most famous images found in the painted Paleolithic caves of France is this antlered wall painting image known as ‘The Shaman of Trois Freres’.

This prehistoric figure of an old man with a bearded face, depicted on the cave wall as dancing in the guise of a horned animal, is said to be the first known visual representation of a Shaman.

Women have, of course - since the very beginnings of human life on the Earth - always also played the vital role of the Shaman in cultures all over the world.

IN THE HORNED MAJESTY OF MY ANCIENT, ANTLERED ANCESTRY

(Stark Trees, Frost Fingers All)

John Shane

(Westhope Common, Herefordshire, 1978. Photo: John Shane: )

I.

Stark trees

frost fingers all

creak and groan

in the twilight

- the crack and crunch

of boots on frozen puddles

diamond dappled

covered in crystal dew

All becomes ‘as if’

unreal, a landscape

hung with jewels

Clear sky, bright

beyond the rolling hills

- the air as sharp as needles

stinging cheeks and brow

breath steaming

ahead of me

Winter walks

veiled in mists

and mysteries

‘Will leaves

really come again

upon those bitter trees?’

‘Will Summer’s sun

and sweet soft rain

again bless these

bleak snow-covered fields

to bring forth

summer’s bounty?

The dark does not answer

at the ending of the day

the season does not

know it’s name

nor the counting

of the days

The blackbird

yellow-beaked,

bright-eyed,

sings a moment

by my door

then ups

and flies away

Dawn has its

special flavor

and the night; dusk

does not remember

cannot forget

The dark has no sooner

settled in, that it

gives birth to light

II.

Bright fire

burning

in the hearth

The night is quiet

Darkness all around

and snow falling down

Move closer to the fire

Look..! Who’s there…?

Listen!

Flickering flames

dance up in primal ecstasy

revive

tribal memory

of my own cell’s

prehistory

I drink amber whiskey

bought in airport

Charles de Gaulle,

Paris,

several days ago,

and think of relativity

of time and place

Last week,

Paris;

now back home in

the heart

of rural England

enclosed in this cottage,

this small, warm space

high on a hill

in Herefordshire

shut in by white snow

and black night

Snow still falling;

How quiet it is outside!

Winter’s iron grip

icy on the wind

shakes my hand

Water, frozen

in falling form

settling soft

as sky-fleece

North star,

north wind

and waning moon

sing no song

tonight

All is silent

snow-bright

But beneath the crisp

earth crust, the soil

is still warm

and there

the mothered seeds

unfold slow

Something stirring:

the sap of Spring

already pulsing,

and Earth,

turning in her sleep,

sighs deep

as Winter’s death

gives birth

to Spring’s anticipation

Thus the dream renews,

regenerates,

through the dark

slumber of the Winter’s womb

III.

In the horned majesty

of my ancient

antlered ancestry

I am the drum-beat

cloven-hoof

cave-heart lord

of solemn shaman

sympathy

I dance on fire

ember-eyed and aged,

ever-young, renewer

of energies

Shedding my several

shrunken selves,

entering into my

archetypal form,

my skin becomes

the sky, my eye the bird,

my arm the axe,

my tongue the dog,

those mountains my back,

my shadow that tree,

my legs that track!

I become one with the energy

that spins the planets round

makes the Earth turn

causes the sun and moon to rise

water to flow,

fire to burn

Beware the swift, soft stroke of my song!

It’s power can pierce the heart

and make a strong man weak

or make a weak man strong,

make the day seem half as short

or the night seem twice as long!

My words transform the leaden

into purest gold, and open space

for vision of that which

no man or woman

dares behold

Entering the mysteries

dark secrets are revealed:

nothing will remain

that can be concealed

By this inspiration

my breath becomes

like lightning:

I expand, explode,

dissolve,

spitting and spewing stars,

shitting out whole universes,

pissing galaxies,

until finally done

coupling with the sky

uniting with space

I come in constellations

in love’s infinite embrace

forever face to face

creator and destroyer

all in one

dark and light

man and woman

sun and moon

in me unite

dancing in energy’s

eternal delight

And you who

read these lines

in another place

another time,

before you judge this poet

mad or sane,

look into your own mind;

look well,

and look again

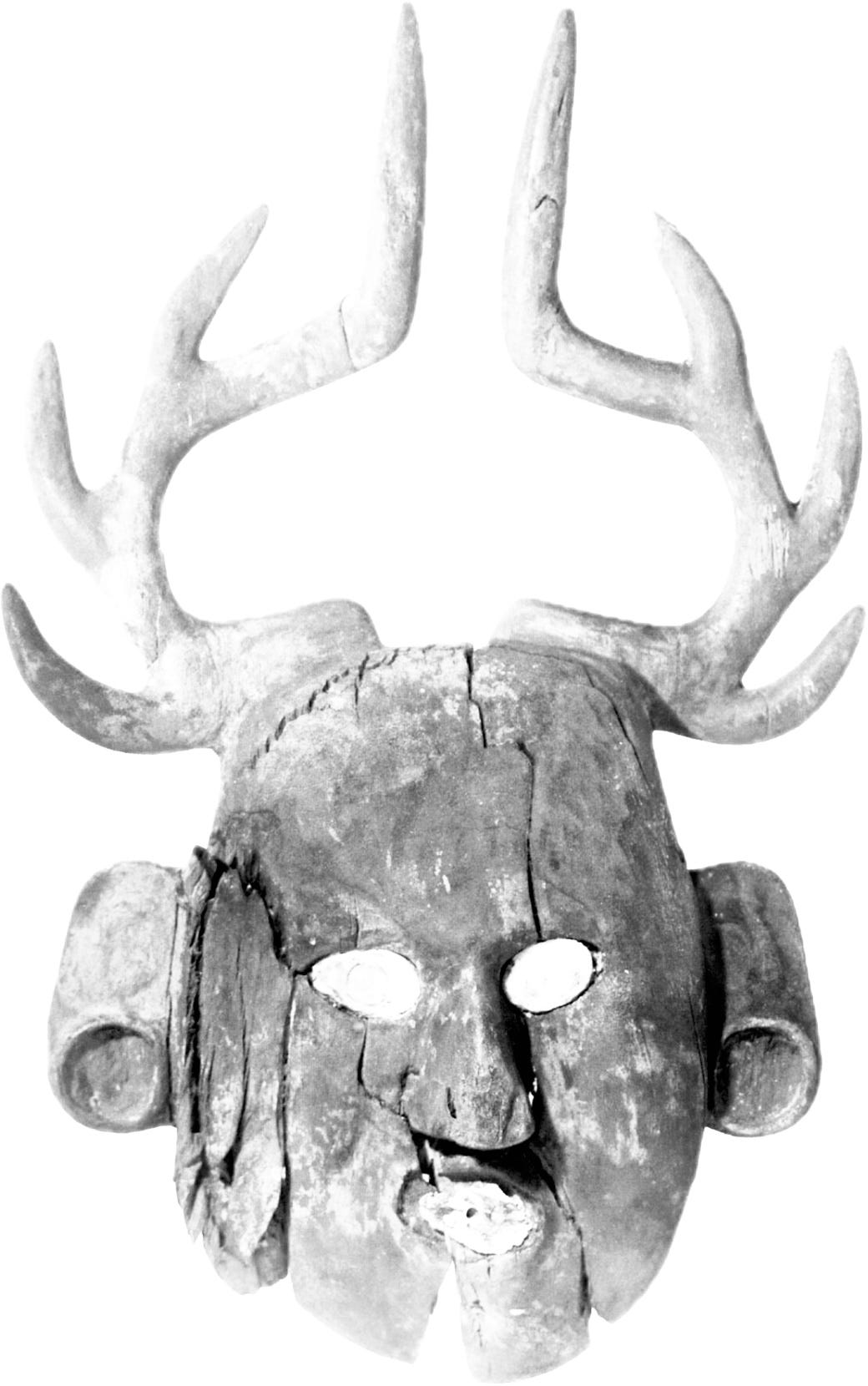

Visionary Shaman’s mask from Spiro Mound, Leflore County, Oklahoma. The surface of the face was originally painted; shell inlays have been lost from the earlobes.

The photo above was taken at the time I wrote ‘In The Horned Majesty Of My Ancient Antlered Ancestry (Stark Trees Frost Fingers All)’ while I was reading poetry at an event at Oxford University.

COMMENTARY and CONTEXT:

Returning home after meeting Chogyal Namkhai Norbu for the first time at two retreats in London and Paris

I wrote this poem in 1978 by the fire in a small isolated old thatched cottage in Herefordshire as the surrounding English countryside was completely covered with deep snow and ice.

That powerful snowstorm hit Herefordshire immediately after I’d returned home from attending two retreats, one in London and one in Paris, with the great Dzogchen Master Chogyal Namkhai Norbu, who I’d just met in London for the first time and who I recognised at once would be a very important teacher for me.

47 years later, at the start of the new year of 2025, another wave of snow and ice has closed roads all over England and has brought back the memory of what happened during the harsh winter in which I wrote the poem, leading me to want to publish it here for the first time.

An inauguration into personal rather than political power:

Laying claim to the ancient roots of my art, an art that predates the arrival of writing and has existed from the time of the very origins of the gift of language

That dark winter night in 1978, surrounded by snow and ice, as I wrote my poem, I entered into a state of powerful concentration, and then I went beyond that state of concentration, entering in full undistracted awareness into an ‘altered state’, or ‘peak experience’.

In the flow of the vision that arose as I wrote down the poem, I saw myself wearing upon my own head the Crown of Antlers that has been - since time immemorial - the characteristic head-dress of the ancient Shaman poets, and I acknowledge in the poem - firstly to myself, but then to my reader - that, deep down, beneath all my concerns about my ability to write and my doubts about ever being able to match the work of the writers I most admire - I feel fully empowered to embody and practice - in my own time and in my own language - the ancient art that I have made a commitment to try to master, an art that seeks to use words to speak not only of the everyday world of the ‘ten thousand things’, but also to find ways in which language can express the mysteries beyond words and beyond the limited thinking mind.

In the non dual contemplative state, identifying fully with an emerging archetype, rather than bringing about a hubristic inflation, involves the integration into the psyche of genuine psychic knowledge and power, and, in contrast to the corrosive pride of ego, the result of this increase of awareness is known as ‘divine pride’, or ‘vajra pride’, and it brings the relaxed confidence of profound self-respect.

The wind blew snow over my cottage,

The fire roared in the hearth.

And my mind and heart were filled with awe

at the wonder of the world.

( Below you can read a little more about my cottage in Herefordshire, how I came to live there, and how I began to work there as a teacher of Creative Writing through The Arts Council of Great Britain. And, after that, at the end of this post, you’ll find some technical notes on the mental states involved in the writing of the poem. )

(Birches Knoll, Westhope, Herefordshire, 1978. Photo: John Shane)

Above is a photo of ‘Birches Knoll’, my 400 year old thatched cottage home in 1978, situated on Westhope Hill, deep in the remote countryside of rural Herefordshire, close to the border between England and Wales.

When I bought the cottage at a local auction for the princely sum of £4,750, it had two acres of land and two ramshackle barns, but it had no indoor toilet and the household water supply was furnished by the slow process of winding down an empty galvanised-iron bucket into the old well in the garden and then winding the now heavy bucket up again on the end of it’s long iron chain.

Strangely, even though the cottage’s name refers to birch trees, there was not one birch tree anywhere on the property.

But, as you can perhaps just about make out in the photo above, there were three large and very old yew trees in the garden.

So, if there was ever a place that you might reasonably expect to be called ‘Yew Tree Cottage’, it was this one.

It was a tiny space with one bedroom and a landing bedroom at the top of the simple wooden ladder-like stairs, and a living room with a huge fireplace and a simple kitchen downstairs.

But I’d been living for a year and a half traveling around England living in a traditional old brightly painted wooden Romany gypsy caravan while I read poetry and played music at folk clubs in pubs and at other small venues, and the cottage was four times as big as the caravan, so, in comparison, my new home felt spacious to me.

And anyway, like the people who built the cottage of local sandstone dug out of the surrounding hillside with a thatched roof of Norfolk reed, I kept the front door open most of the time and spent much of the day outdoors in both winter and summer.

Living in my old caravan, I became a true nomad as I learned to travel light with few possessions and to be ready to pack up and move on at a moment’s notice. I was never in one place for long enough to get to truly know it.

The road was what I knew.

Living at Birches Knoll, I truly inhabited one place in the countryside and came to know that place intimately in all seasons.

After growing up in London, through living and traveling in my gypsy caravan and then settling for several years at Birches Knoll, I entered into a new relationship with nature.

Limiting my needs to a minimum, I tried to live as frugally as I could so that I would be able to survive as someone who knew they would have to adapt their life to match their vocation, because - as everyone was always telling me when I was young - ‘you don’t make money from writing poetry’.

I took seasonal work picking fruit on the local Herefordshire farms, often apples for the Hereford-based Bulmers Cider company, but also picking strawberries for local farmers, and I continued to meet and enjoy the company traditional nomadic traveling people, including Romany gypsies, who also picked fruit in the fields and sold their wares in Hereford City’s famous old ‘Butter Market’, about which I wrote a long-form poem with the title, ‘The Celebration Of The Butter Market’, that was published as a book by West Midlands Arts, the local branch of The Arts Council Of Great Britain.

Gradually, after my work came to the attention of West Midlands Arts, I was able to increase my income as I began to get work through the Arts Council Of Great Britain itself, whose ‘Writers In Schools’ scheme sent me around the UK to teach Creative Writing classes to all ages of pupils, and through the National Poetry Council of England which, at the time, arranged readings for poets around the country, who sent me to readings in all manner of venues.

At the same time, I formed a band to perform my songs and we began playing in pubs and clubs - at first mainly up and down the Welsh border country and the West Midlands - but, after we recorded an album of my songs with the title ‘Cross My Palm With Silver’, I began traveling further afield.

I was, at the time, by no means alone as a well-educated young person brought up in a big city - in my case London - who found the prospect of buying a home there too expensive and wanted to move to the country to find a less financially-demanding and more ecologically-sound way of life in closer contact with nature.

A major ‘back to the land’ movement going on back then.

Westhope Common, Herefordshire, Winter 1978.

While it’s true that my cottage had had only two acres of private land of its own, it enjoyed the great advantage of being surrounded by 300 acres of common land on the top of Westhope Hill, from where, on a clear day, you could sometimes see the Black Mountains, across the border in Wales. (photo: John Shane).

SOME NOTES ON THE WRITING OF THE POEM:

The poem is in three parts:

Parts I and II: provide simple notation that creates images - in words - of what was happening and what was arising in my mind moment by moment

In its first two parts, the poem begins with a series of simply-stated stanzas notating what was happening, moment by moment, during the time that I was snowed in inside my small and remote cottage.

I had just attended two retreats in which we listened to Chogyal Namkhai Norbu explaining the Dzogchen teachings, and together practiced the specific methods of Semde series of the Dzogchen teachings.

Using the act of writing as a practice to enter ‘Access Concentration’, the bridge between a state of Distraction and the state of Non-Distraction

When one is following and applying the Semde series of the Dzogchen teachings, one maintains a basic practice of self-observation, and, if one notices that one has become distracted from the ‘Natural State’ in which the mind is spontaneously free, and has, instead, become caught up in one’s thoughts and emotions, one needs to adopt a method - such as fixation on an object followed by fixation without an object - to enter what is called in some traditions ‘Access Concentration’, the focused entry point through which one can more easily enter into the state of contemplation, and as I sat with pen and paper in my old cottage in front of a log fire, the act of writing down long-hand the images that you can see or hear in the first two parts of the poem served as a concentrative method that brought my mind into focus in the moment.

Then, while I was sitting writing in the state of focused yet relaxed meditative concentration that is evident in the descriptions of my external surroundings in first two stanzas of the poem, I entered - in full awareness - into a deeper, level of consciousness, and the inward experience of that altered state of consciousness is described in the third part of the poem as I attempted to set down in words what I was experiencing, without becoming distracted by the flood of archaic psychic content that was surfacing from the unconscious into consciousness which required me to use ‘transgressive language’ to express what I experienced as I went beyond the limits of ordinary waking consciousness.

In the Dzogchen teachings, what is referred to as ‘The Natural State’ is not an ‘altered state’

‘The Natural State’ itself is never lost; it is the basic unmediated quality of our essential being.

This ‘Natural State’ is always there even when one is distracted, in the same way that the sun is still there even when it is covered by clouds.

But when one is distracted by one’s thoughts, by disturbing emotions, or by events, one can lose the experience of ‘The Natural State’,

Since ‘The Natural State’ is the basic state of our being when we are not distracted, it is not an ‘altered state’.

In fact, it is the only unaltered state.

From the point of view of ‘The Natural State’, even the normal everyday waking consciousness in which one can get lost in thought and caught up in emotions is seen to be an ‘altered state’, because in that state of distraction from the pristine clarity of one’s fundamentally pure ground awareness, one has altered the experience of ‘The Natural State’ of one’s authentic being.

Release Upon Inception - the fundamental characteristic of ‘The Natural State’, also known as ‘The Uncorrected State’

After one has experienced ‘The Natural State’ through Direct Introduction from a Dzogchen Master in a ‘pointing out instruction’ - or other means of direct, symbolic, or oral transmission - one applies methods to confirm that one’s experience of ‘The Natural State’ is authentic, and then one continues in that state with no need to ‘practice’ unless one has become distracted.

In the total relaxation of ‘The Natural State’, any thought, emotion, or event of any kind that arises in one’s awareness, spontaneously self-liberates in the moment of its arising, without any effort. This is called ‘release upon inception’. No ‘practice’ is required. Everything is left ‘as it is’, and for this reason, ‘The Natural State’ is also referred to as ‘The Uncorrected State’. Nothing has to be done or not-done. The image used to illustrate this is that of a snake automatically and spontaneously uncoiling of its own accord, unraveling - with no need for any external agent’s help - any knots that may have formed in itself.

Remaining undistractedly in ‘The Natural State’ while at the same time experiencing an altered state of consciousness

So, ‘The Natural State’ is not an ‘altered state’.

But, if one has the capacity, one can access altered states while remaining in ‘The Natural State’, and the third part of this poem is a record of my entering an altered state and remaining in ‘The Natural State’ undistracted by what was arising in my awareness.

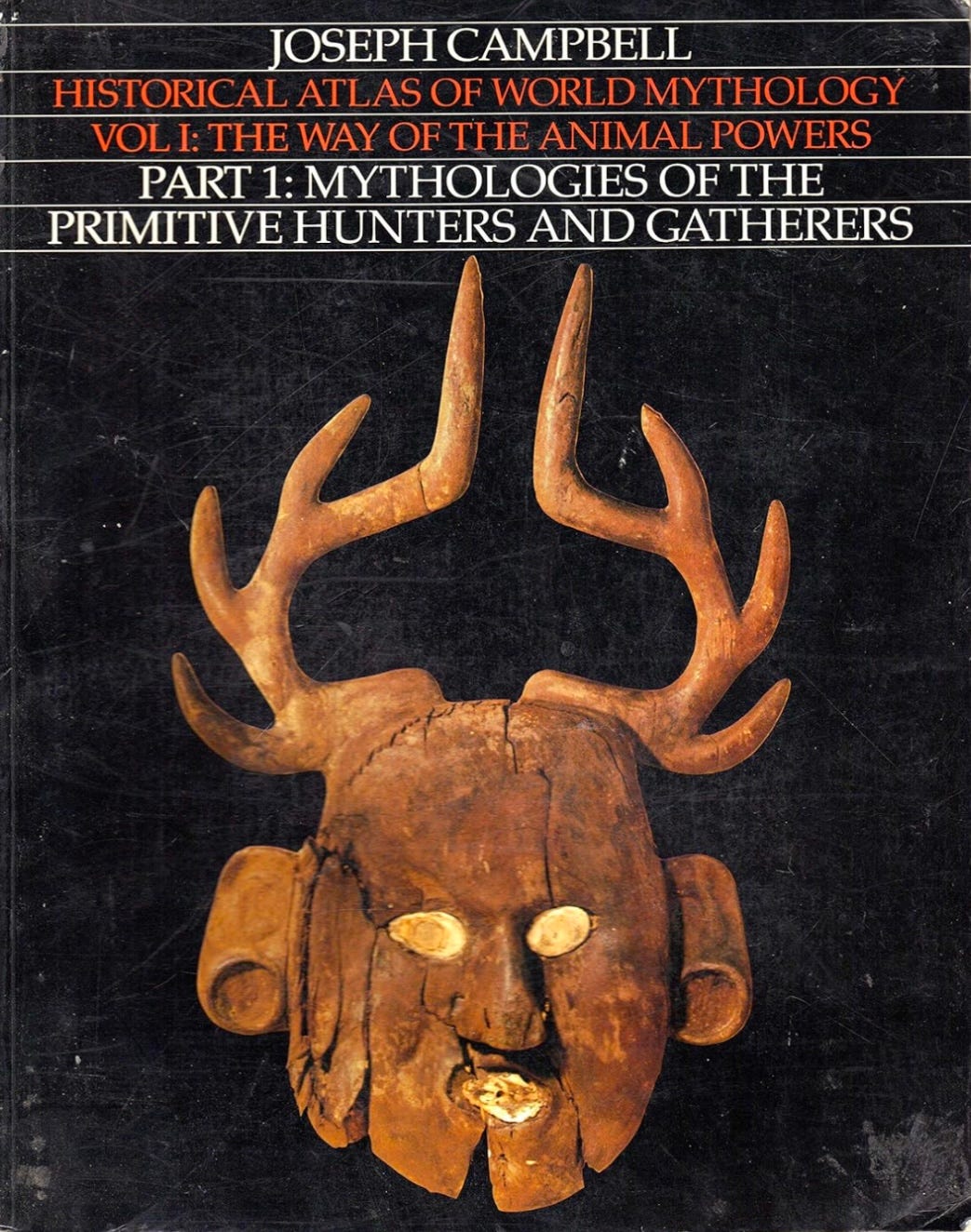

Suggested further reading: ‘The Way Of The Animal Powers’, Volume 1 of Joseph Campbell’s Historical Atlas Of World Mythology that details the myths of Paleolithic hunter-gatherers all over the world which focus on shamanism and animal totems.

"At the heart of ‘The Way of Animal Powers’ is a masterful presentation of shamanism and a portrayal of those animistic cultures that have survived into modern times" the Bushmen, Pygmies, Andamanese, Tasaday, Australian Aborigines, Native Americans, and many others. This volume culminates in a thorough examination of the mythologies, rituals, and traditions that were everywhere in evidence during the twilight of the Paleolithic Great Hunt. The volume itself is a consummatae example of the art of bookmaking. Campbell's scholarly and readable text is integrated throughout with a profusion or color plates, specially-commissioned full-color maps. outstanding black-and-white photographs, unique drawings, and numerous illuminating charts."- from the Publisher, Harper and Row, San Francisco, 1983.