MY HEART IS ALL AT SEA ONCE MORE (The Unexpected Victory Of Poetry) - John Shane + Where’s Winston’s fiery oratory in defence of our liberties today? How his love of language inspired my own as a boy

READ & LISTEN TO A 2009 POEM ABOUT A SMALL VICTORY FOR LOVE IN THE INTIMATE WAR OF THE HEART AND READ CHOGYAL NAMKHAI NORBU’S ADVICE TO YOUNG LOVERS ON HOW TO BEHAVE TOWARDS EACH OTHER

CLICK ON THE PLAY BUTTON ABOVE at the right hand side of the page to listen to John Shane read his ‘My Heart Is All At Sea Once More (The Unexpected Victory Of Poetry)’.

‘The ultimate aim of a poet should be to touch our hearts by showing his own..’ THOMAS HARDY

OK…so you wrote, ‘my heart is all at sea’, but what does that really mean, anyway…? READ ON TO FIND OUT….

‘What am I doing here..?’ John Shane on retreat while living in a cave in Nepal near Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha.

In the elegant hotel described in the poem, the writer - who had, at that time, been living an itinerant life for years, first touring to perform as a poet and musician in Great Britain, and then traveling to retreats around the world, often acting as the translator for the late Dzogchen Master Chogyal Namkhai Norbu, finds himself asking, ‘What am I doing here..?’ in such a luxurious place, where Royals take their tea…

‘What am I doing here..? In the photo above, CHOGYAL NAMKHAI NORBU - to the delighted after dinner amusement of participants at a retreat held in 1980 at a resort hotel in Monte Faito that overlooks Mount Vesuvius, near Naples, Italy - asks John Shane (wearing a black cotton jacket with silver embroidery that he sometimes used to wear on stage in the days when he was performing with his band) to improvise - on the spot ! - and sing, for a whole hour, one poem or song after another…no repetition allowed. Many of the resulting spontaneous songs and poems were humorous inventions about the young men or women present in the room….This kind of after-hours activity, always with different people being in the ‘hot-seat’, was typical of how Chogyal Namkhai Norbu encouraged his students, who came from many different countries, ethnic groups, and walks of life, to open up to each other as the Dzogchen Community began to form…

Norbu Rinpoche didn’t only give Dzogchen teachings. When asked, or when he considered it necessary, he would also advise his students in detail on intimate matters of the heart and on practical matters of their daily lives, and I intend to write in a future post more about his interactions with me in various situations and the advice he gave me.

Hmmm…? The subtitle of the poem is ‘The Unexpected Victory of Poetry’. What’s that all about?

Well, the famous ‘V for Victory’ sign that Churchill made with the fingers of his right hand was, of course, one of the key visual images of his iconic wartime image, along with his hat and cigar.

But the poem hints at hope for the ‘victory of poetry’ - the language of the heart that speaks of the ‘war’ of love - over the political rhetoric of Churchill’s speeches that was necessary to wage and win a bloody war against tyranny.

After choosing this particular poem from all the poems in my archive to post here and then after sitting in front of my vintage Neumann U47 microphone to record it, as I was listening back to the recording of my own voice reading the poem, I found myself thinking of Churchill and identifying with him sitting in front of a very similar microphone during World War II - and of my parents listening to him on the radio.

CLICK ON THE PLAY BUTTON ABOVE to listen to a clip of Winston Churchill’s famous first speech to the House of Commons as Prime Minister, given on May 13th 1942: “….I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.”

‘What am I doing here….?’. My parents must have asked themselves that question, too, in London at a time when bombs were raining down on them during the Blitz, as can be seen in archival clips included in a new documentary series ‘Churchill At War’ that I discovered, after recording this poem, is now streaming on Netflix.

As Churchill delivered his wartime speeches in London, my parents were living under the savage nightly bombardment of the Luftwaffe during the Blitz.

Two years before my own birth just after the end of the war, my father was the commander of an antiaircraft battery trying to shoot down the V2 rockets that were coming in every night. He said that the most terrifying moment was when a V2 was overhead and it would suddenly go silent, which told him and his men that the rocket’s motors had switched off and it was about to come down on its target - them.

Meanwhile, my mother, along with my elder brother - a baby born when a bomb fell during the last years of the war, the shock of which caused my mother’s waters to break - would be sheltering for the night far down below the street level of the city, sleeping, among many others, on the platform of the local underground station.

My father and mother would have been listening, along with the rest of the population of the country and millions of people around the world to Churchill using the power of language to try to lift the morale of the British people and to rally the Allied troops in their fight against Hitler and the Nazi armies all over Europe and North Africa, etc.

And, after the war was over, when I was a boy, knowing that my parents had listened to those speeches at such a time of crisis in their lives, Churchill’s use of language had a profound influence on me, and that’s why - during the events of the night in 2009 that is described in the poem you can listen to here - seeing the photo of Churchill in the hotel lobby where I went to meet my lover had such a powerful effect on me.

‘What am I doing here…?’ This is not the photo in the hotel lobby in the poem.But below, in is own words, you can read Yousuf Karsh’s story of how he came to take this classic portrait of Churchill in 1941:

“My portrait of Winston Churchill changed my life. I knew after I had taken it that it was an important picture, but I could hardly have dreamed that it would become one of the most widely reproduced images in the history of photography. In 1941, Churchill visited first Washington and then Ottawa. The Prime Minister, Mackenzie King, invited me to be present. After the electrifying speech, I waited in the Speaker’s Chamber where, the evening before, I had set up my lights and camera. The Prime Minister, arm-in-arm with Churchill and followed by his entourage, started to lead him into the room.

I switched on my floodlights; a surprised Churchill growled, ‘What’s this, what’s this?’

No one had the courage to explain. I timorously stepped forward and said, ‘Sir, I hope I will be fortunate enough to make a portrait worthy of this historic occasion.’ He glanced at me and demanded, ‘Why was I not told?’ When his entourage began to laugh, this hardly helped matters for me. Churchill lit a fresh cigar, puffed at it with a mischievous air, and then magnanimously relented. ‘You may take one.’ Churchill’s cigar was ever present. I held out an ashtray, but he would not dispose of it. I went back to my camera and made sure that everything was all right technically. I waited; he continued to chomp vigorously at his cigar.

I waited. Then I stepped toward him and, without premeditation, but ever so respectfully, I said, ‘Forgive me, sir,’ and plucked the cigar out of his mouth. By the time I got back to my camera, he looked so belligerent he could have devoured me.

It was at that instant that I took the photograph.” (Yousuf Karsh.)

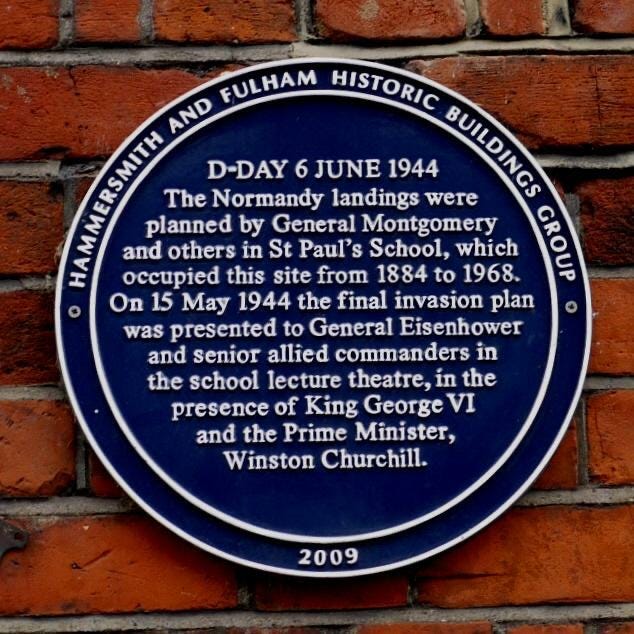

When I was at my secondary school in London, before classes began each day, I used to complete my homework in the very same room in which, in World War II, General Montgomery, who had himself been a pupil at the school, together with HM King George VI, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and US General Eisenhower, completed the final plans for the D-Day Landings in Normandy.

In all, Churchill wrote more words than the combined output of two other great English writers - Shakespeare and Charles Dickens - and he won the Nobel Prize In Liberature.

When I was 14 years old at my secondary school, London’s elite St Paul’s School, I also won a prize for my writing, albeit a very much less prestigious one than Churchill’s Nobel Prize, and the books that I received as my little prize were two volumes of Churchill’s writing - his ‘Collected Speeches’ and his ‘History Of The Second World War’, which I began to read with great interest, the cadences of his prose entering my mind and becoming fixed there, where they mixed with the words of all the other writers I read in my childhood and adolescence.

The photo above shows a plaque that is still fixed to the one remaining wall of the garden of the old St Paul’s School in West Kensington commemorating what took place, two years before I was born, in one of the rooms in the now demolished buildings of St Paul’s school, where I studied as a boy and a young man.

Reading Churchill’s writing was not the only way in which he became an influence on me. While I was at St Paul’s School, in addition to reading Churchill’s books and listening to recordings of his speeches, after I had arrived at the school on most mornings, I would sit to complete homework assignments and essays in the lecture theatre of the now demolished building which - as is commemorated in the plaque in the photo above - was used by Field Marshall Viscount Montgomery (as he became after the war) who was a former pupil of the school - to complete the final plans for D-Day landings in Normandy.

So, for five years, I used to sit each school day in a room below a very large oak panel fixed to the wall into which was carved writing, in gold capital letters, that told the story of how, in that very same room, General Montgomery worked together with HM King George VI, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and General Eisenhower.

So, of course, the knowledge that I was completing my homework in a room in which those illustrious and iconic figures had worked on matters of such historic importance had a profound effect on me and on my sense of myself at that impressionable young age.

Later, of course, I learned more about world history and about aspects of Churchill’s colonialist, imperialist attitudes and political actions that show his life and his work in a different, and much less flattering light, but my interest here is in his use of language and the effect of his language on me as a boy.

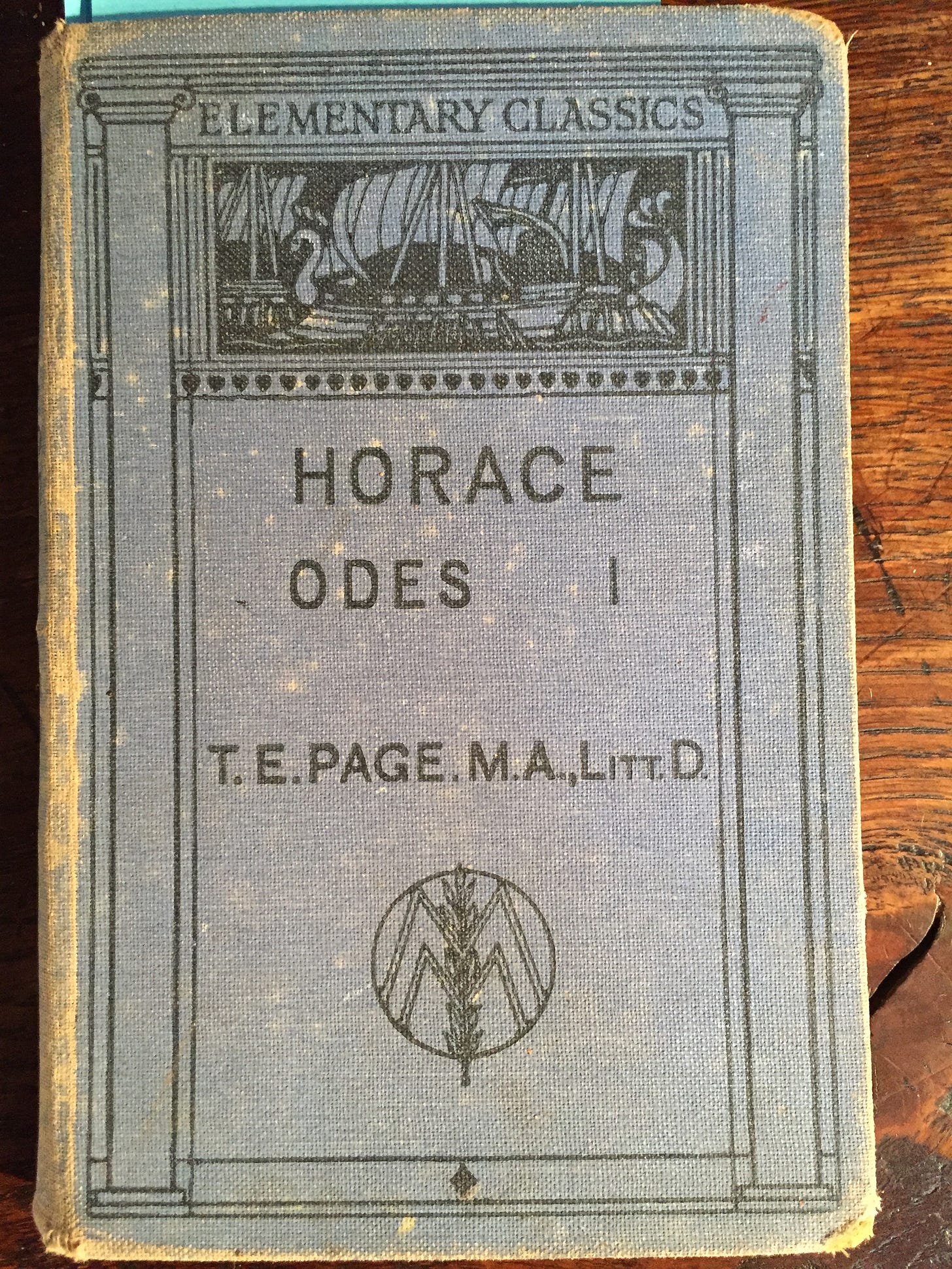

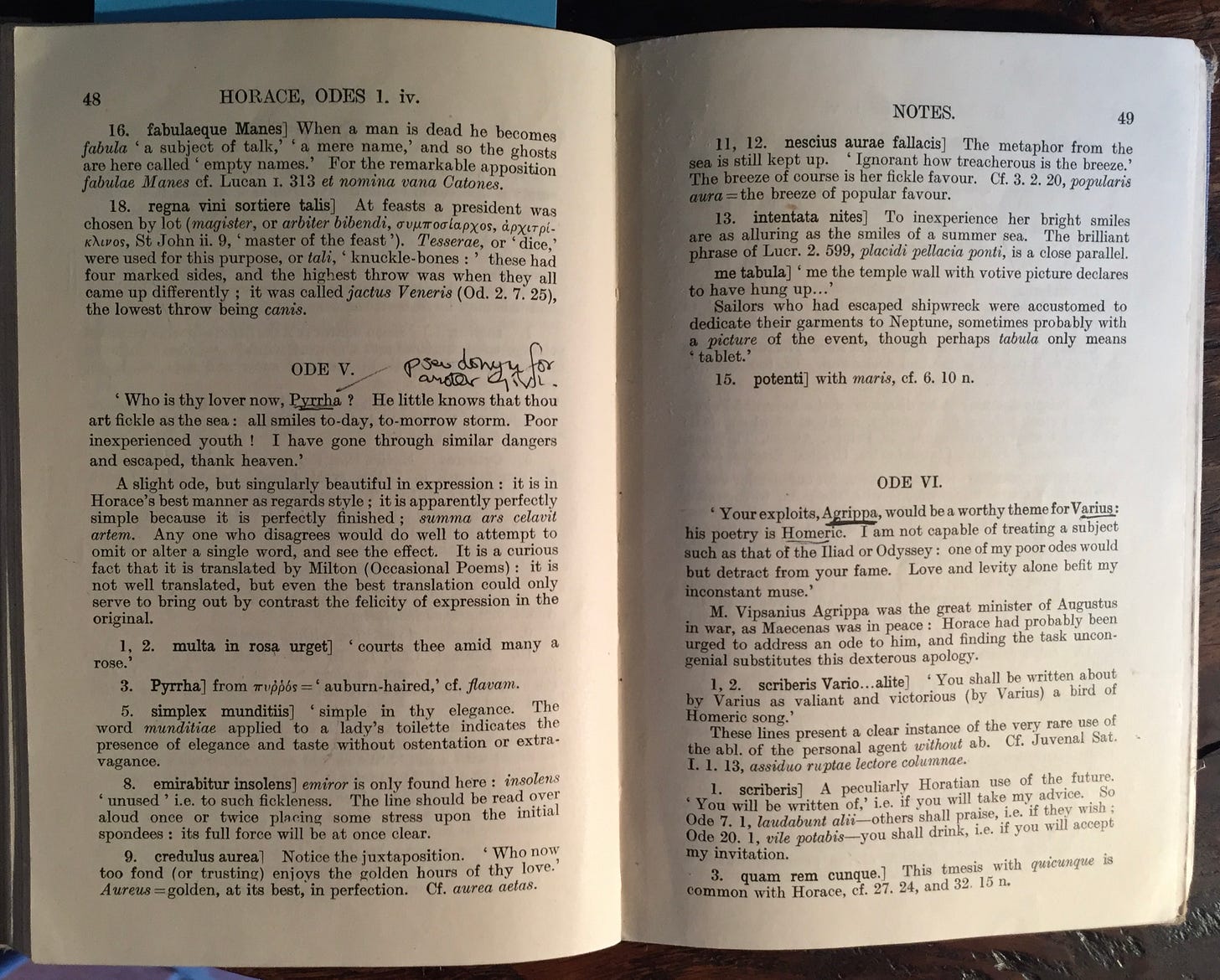

My Classical studies: As a teenager, just beginning to take the risk of asking girls to go out with me, as part of my coursework at St Paul’s School, I had to translate Horace’s Odes, and in particular, Ode number V, ‘To Pyrrha’, a poem in which Horace seems to declare that, after many adventures, now that he’s old, he has given up on love.

So, how do I feel - now that I myself have arrived at 78 years of age - about the same famous poem in which Horace says goodbye to the days of his love affairs ..?

I chose to focus in this article on a poem that I wrote in 2009 about a new relationship that I was just beginning to accept was becoming a deeply intimate one, and, in the same way that, in my last post, I asked myself how I feel now, as a man nearing 80 years of age, about a poem I wrote as a young man that talks about death and dying, I am also asking myself here - after listening to playback of audio of me reading this poem about a love affair that began 16 years ago - how I feel, as an elderly man, about affairs of the heart.

In that regard, I remember hearing Leonard Cohen onstage during one of his wonderful final concerts remarking humorously that, as he approached 80 years of age, he had reached a point at which women found him ‘cute’ as an elderly man rather than being physically attracted to him in the way that they once had been.

I don’t know if anyone finds me cute, or if I care much about that, but I am aware of how my own physical sense of myself has changed as my body has aged, and when thinking about those changes, I’m reminded of my studies at St Paul’s School, where I won a Senior Scholarship in Classics and History, and was required to translate Julius Caesar and the ancient Roman poets into English from the original Latin.

I remember very clearly how I felt, as a teenager, wrestling with the onset of the usual raging hormones, when I read and translated Horace’s Ode number V, ‘To Pyrrha’

I also remember that when my later teacher Chogyal Namkhai Norbu had mainly young people as his students, many of whom were single and were likely to be interested in people of the opposite sex attending his public talks or retreats, he often used to say in his talks, ‘You young people should love like old people. Don’t just be governed by your passions. You may be young, but you should look after each other the way an old couple who have been together for many years look after each other.’

And he also used to say, ‘You can be together, but you can also separate. But it you separate, you must always respect each other.’ That advice may seem banal, but given how people behave towards one another, it’s actually quite radical in its simplicity.

Horace wrote in his Ode To Pyrrha that he had hung up his wet clothes and would venture no more on the stormy seas of love.

Human beings tend to crave certainty. But there is much to be said for living with uncertainty.

It’s 16 years since I wrote, ‘my heart is all at sea once more’, and to be ‘all at sea’ in the terms of Horace’s Ode to Pyrrha, means to be willing to take the risk of loving, without fear of the outcome.

To love always opens us up to the possibility of loss.

In my poem, I wrote that I was willing ‘after all the many shipwrecks that had come before’ to take that risk again.

Even if the loving in which I’m involved now as an elderly man is not based so much on the passions, still there is a risk of loss from venturing forth on the high seas of caring for others.

Come what may, I’m still committed to taking that risk.

In the writing in my archive, there are pieces in which I express my care for others in the terms of personal relationships, but there are also other pieces in which I express the same care for others in the political sphere of our communal life and sometimes I express myself as forcefully as Churchill did in the speeches that I read and listened to while I was growing up.

I do not write from the point of view of any political party or group, yet there is still a risk involved in publishing more political pieces. But, it’s a risk I intend to take in future posts.

Opposing external tyranny, as Winston Churchill did, is necessary.

But if one attempts that kind of activity in the world without at the same time (if not first) addressing the internal tyranny of one’s own ego-centred thinking and action, one risks falling into the error that another Nobel Prize In Literature winner, Bob Dylan, wrote about in his song ‘My Back Pages’, the song in which he famously turned his back on the role of being the political ‘spokesman of a generation’ and began to focus his songwriting on the personal rather than the political.

In ‘My Back Pages’ Dylan sang, “…In a soldier’s stance I aimed my hand at the mongrel dogs who teach, fearing not I’d become my enemy in the instant that I preach’.

I believe that I am in a personal space now from which I can publish what I’ve written on more political themes without hatred and prejudice and therefore without becoming as bad as those whom I oppose. Many of my more political pieces are, in any case, written ‘in character’, as are the political pieces, for example, in Shakespeare’s plays, and I hope, in the coming months, to publish here the voices of characters I have created over the years. My work does not, of course, have the power or the reach of Winston Churchill’s speeches or his other writings, let alone Shakespeare’s or Dickens’, but still - in fulfillment of my vocation as a poet - ‘I will offer up my song for whatever blessings it might bring’, as I wrote in a poem you can find on these pages.

I still have the copy of Horace’s Odes that I used at St Paul’s School to make my translations of his poems from Latin into English.

The page of my textbook, open to show Ode V, ‘To Pyrrha’, with some handwritten notes I made on the page as a schoolboy.

There are many translations of ‘To Pyrrha’ that render the poem in very different ways. I no longer have a copy of my schoolboy translation but I’m going to include two versions here. The first is John Milton’s famous version, and below that I’ll include a more modern one:

Ode I, 5: TO PYRRHA

By Horace. Translated by John Milton.

What slender youth, bedew’d with liquid odors,

Courts thee on roses in some pleasant cave,

Pyrrha? For whom bind’st thou

In wreaths thy golden hair,

Plain in thy neatness? O how oft shall he

Of faith and changed gods complain, and seas

Rough with black winds, and storms

Unwonted shall admire!

Who now enjoys thee credulous, all gold,

Who, always vacant, always amiable

Hopes thee, of flattering gales

Unmindful. Hapless they

To whom thou untried seem’st fair. Me, in my vow’d

Picture, the sacred wall declares to have hung

My dank and dripping weeds

To the stern god of sea.

Below is a more modern translation of the same poem:

HORACE: ODES 5.1: TO PYRRHA:

Who’s making love to you now, Pyrrha,

What beautiful boy drenched

In aftershave, covered in rose petals in some artist’s basement,

Who are you binding up your blonde tresses for,

So simple, yet so artful? Soon he’ll be looking

Out to sea cursing fickle promises and gods,

Gazing out amazed at the foaming breakers,

The winds whipping them to fury;

Yes, the boy who thinks he has you now - Jackpot!! Pure gold..!!

Who hopes you’ll always be like this,

All his, biddable and available; yet who has

No idea of the treacherous changes of breeze.

Oh I pity those whose image of you

Shines untarnished - who’ve never tried you.

As for me, I’ve come back safe from

Drowning; I’ll venture no more out on the stormy seas.

MY HEART IS ALL AT SEA ONCE MORE

(The Unexpected Victory Of Poetry)

John Shane

Just hours before her

birthday

party

She surprised me

when she phoned

to tell me to dress

that evening

particularly smartly

Because, despite

the fact that

we both live in London

where the party

was to be held

She had, without a word to me

booked a room for the two of us

that night

At one of London's classiest

and most expensive hotels

Where, in the lobby

there is a photo of a smiling

Winston Churchill

getting out of an official car

outside that self-same

landmark front door

just after the Second World War

With his trademark big cigar

but without the usual British 'Bobby'

to provide him with security

And, when I saw this,

I thought -

'Now, there's the kind

of the personal courage

that we need today

And yet, which, in the public sphere

is so little on display

That's the man, after all

who

- despite his many

well-documented faults -

when the nation's back

was up against the wall

Used his inspired

and fiery oratory

to lead the fight against

a brutal tyranny

Helping us all

to remain free…’

‘But what..'

- I wondered then -

'.. has my poor poetry

ever done to free

anyone but me?'

Standing where Churchill stood

I vowed then that

with my much more limited means

I would do what I could

To continue the battle

for freedom that he so

bravely fought

But poets are really

only any good

when they are truthful

in making their report

from the frontline of a

much more intimate war

And, in this regard, I must

make my confession

(even if it might seem to be

a somewhat over-personal

digression from my high theme)

Because, when I came that night

to the hotel bedroom door

and knocked and waited

for my lover's hand to open

I had a moment

of doubt and fear

thinking to myself -

'When so many, in the world

are homeless and starving

‘what am I doing here..?'

But then the door was

opened from within

And, when I was inside

she took off the dress she wore

my fingers touched her skin

and the secret of her essence

shook me to the core

And, no longer clinging

to the quiet safety of the shore

I found myself willing

to put behind me

in that moment

all the many shipwrecks

that had gone before

And make my peace with myself

Finally finding the courage

to accept that

my heart is all at sea

once more

“What am I doing here…?’ CLICK ON THE PLAY BUTTON ABOVE to watch and listen to Bob Dylan, George Harrison, Tom Petty, Eric Clapton, Neil Young and Roger McGuinn all sing and play live together Bob Dylan’s song "My Back Pages" in New York in October 1992 on the occasion of the concert to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Bob Dylan’s musical career. I’m not afraid that, given where I’m now coming from, I will ‘become my enemy’ if I publish , without hatred or prejudice, poems that take on political themes that are ‘worldly’ from a radically spiritual point of view, and I will be doing so in some of my future posts…

Thank you John cmvery very much

A lovely and lovable offering throughout, and I’m echoing the thanks!!